China’s Shandong Port Group (SPG) has privately instructed its ports to ban vessels sanctioned by the U.S. Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) as of January 7. This decision follows a record number of sanctioned crude tankers visiting several major terminals in the preceding weeks, raising concerns about potential disruptions to teapot refiners’ crude imports.

In December and early January, eight OFAC-sanctioned VLCCs discharged 16 million barrels of Iranian crude at Shandong through the ports of Qingdao, Dongjiakou, Rizhao, and Yantai. These shipments accounted for over 30% of Shandong’s sanctioned oil imports during this period.

This surge reflects Iran’s strategy to reduce shipping costs and maximise oil revenues, by cutting profit-shares with middlemen, including shipowners.

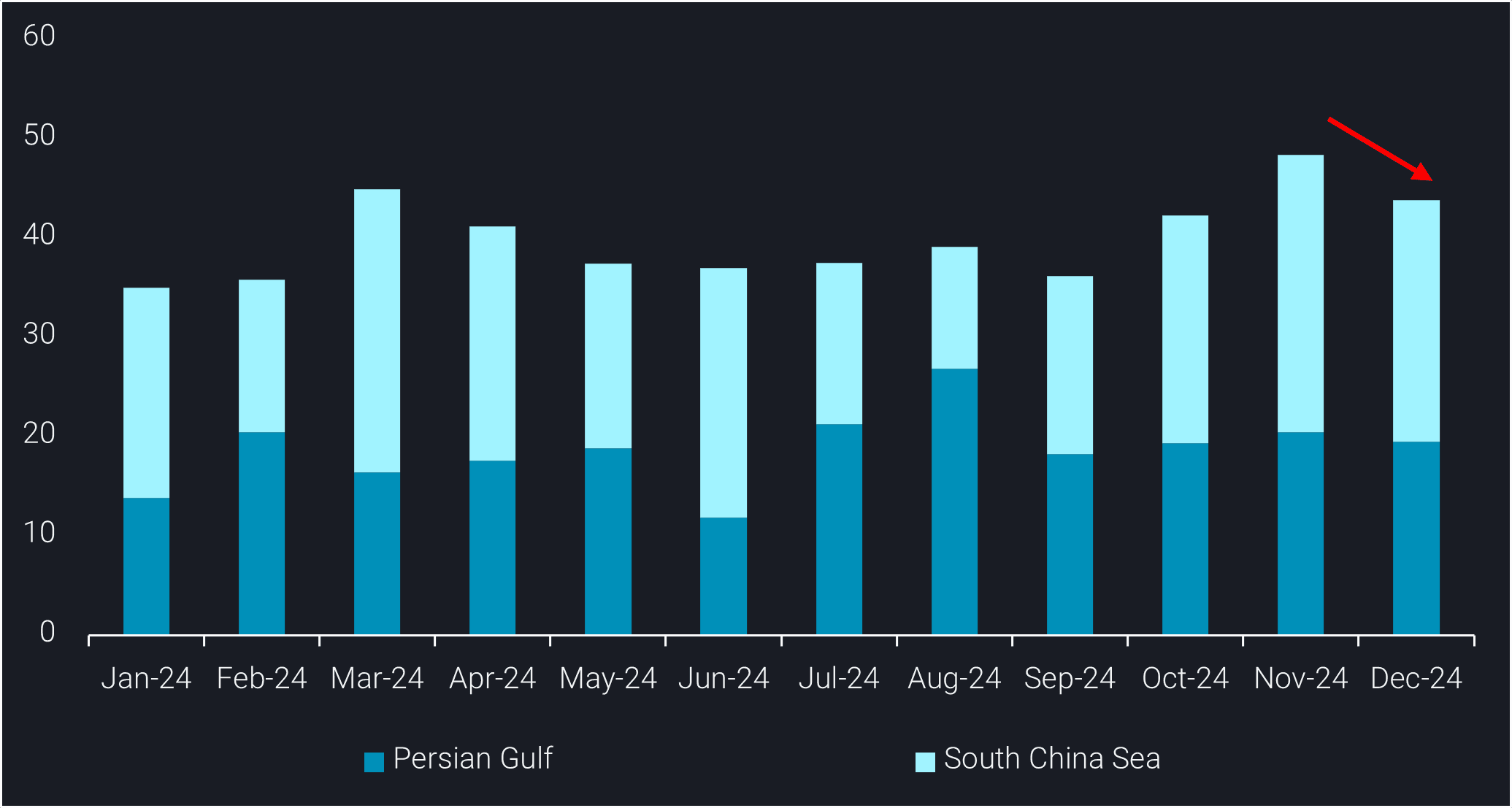

The pressure on teapot refiners to utilise their 2024 crude import quotas (as detailed in our earlier market insight) has fueled this trend. By fulfilling deliveries on sanctioned vessels, Iran avoided the additional costs associated with ship-to-ship (STS) transfers. This approach also helped draw down Iranian floating storage volumes in the South China Sea from, which had peaked in early December.

Iran crude/condensate floating storage by location (mb), calculated by manual analyst assessment

SPG’s decision to blacklist OFAC-sanctioned vessels signals a growing concern that sanctioned tanker visits might become routine. Notably, three of the eight VLCCs were sanctioned shortly before arriving at Shandong in December but were still granted priority unloading.

This raised alarms within SPG about potential risks, prompting the ban as a means to encourage “clean tanker deliveries”. Also, sellers/traders are expected to absorb the additional costs of transferring oil to non-sanctioned tankers, as DES-Shandong Iranian crude cargoes are already priced near the upper limit acceptable to teapot refiners.

In a follow-up notice, SPG suggested that the shipping ban would have limited impact on teapots, noting that most sanctioned oil is currently transported on non-sanctioned tankers. This statement aims to reassure refiners while emphasising the group’s commitment to mitigating compliance risks.

Globally, at least 191 VLCCs are currently servicing sanctioned oil flows, with 95 of these vessels—around 50% of the dark VLCC fleet—on the OFAC sanctions list. While the availability of dark VLCC tonnage suggests sufficient capacity, shipowners may be hesitant to deliver high-risk oil amidst heightened OFAC surveillance. This hesitancy could force Iran to offer higher profit-sharing incentives to shipowners to avoid delays in cargo delivery and potential supply disruptions.

Shandong’s ban coincides with toughest US sanctions on Russia

Although Shandong’s ban on OFAC-sanctioned tankers was prompted by Iran-related activities, it is expected to primarily affect Russian crude imports. This follows US’ implementation of the most severe sanctions on Russia’s oil industry, effective January 10.

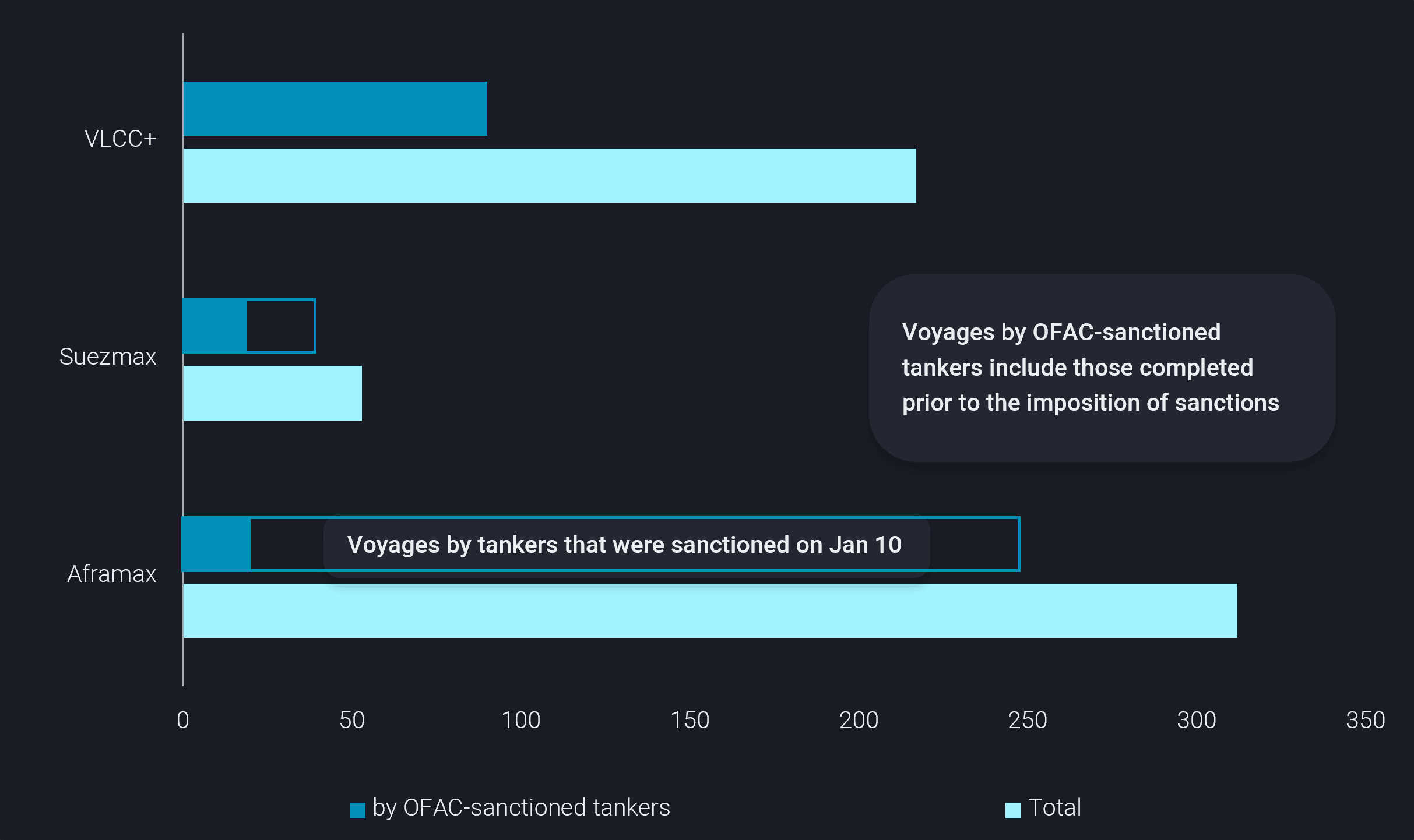

The latest round of US sanctions adds 77 Aframaxes and 25 Suezmaxes to the OFAC list, designating much of Russia’s primary crude fleet. This significantly hinders Russian oil deliveries, especially for barrels originating from Russia’s Far East. In 2024, 50% of these barrels were delivered to Shandong, with another 40% headed to other Chinese ports.

Over 85% of Russian crude voyages into Shandong in 2024 were conducted by tankers now sanctioned by OFAC. If Shandong’s ban takes immediate effect, these vessels may no longer be able to serve their Shandong customers, creating logistical challenges even for January-delivery cargos.

Chinese buyers, including Shandong teapots and state-run refiners in other provinces, are unwilling to bear additional shipping costs, especially as January ex-ship cargoes were settled at around $1.5/b above Brent futures, compared to the deeper discounts seen for September and October deliveries.

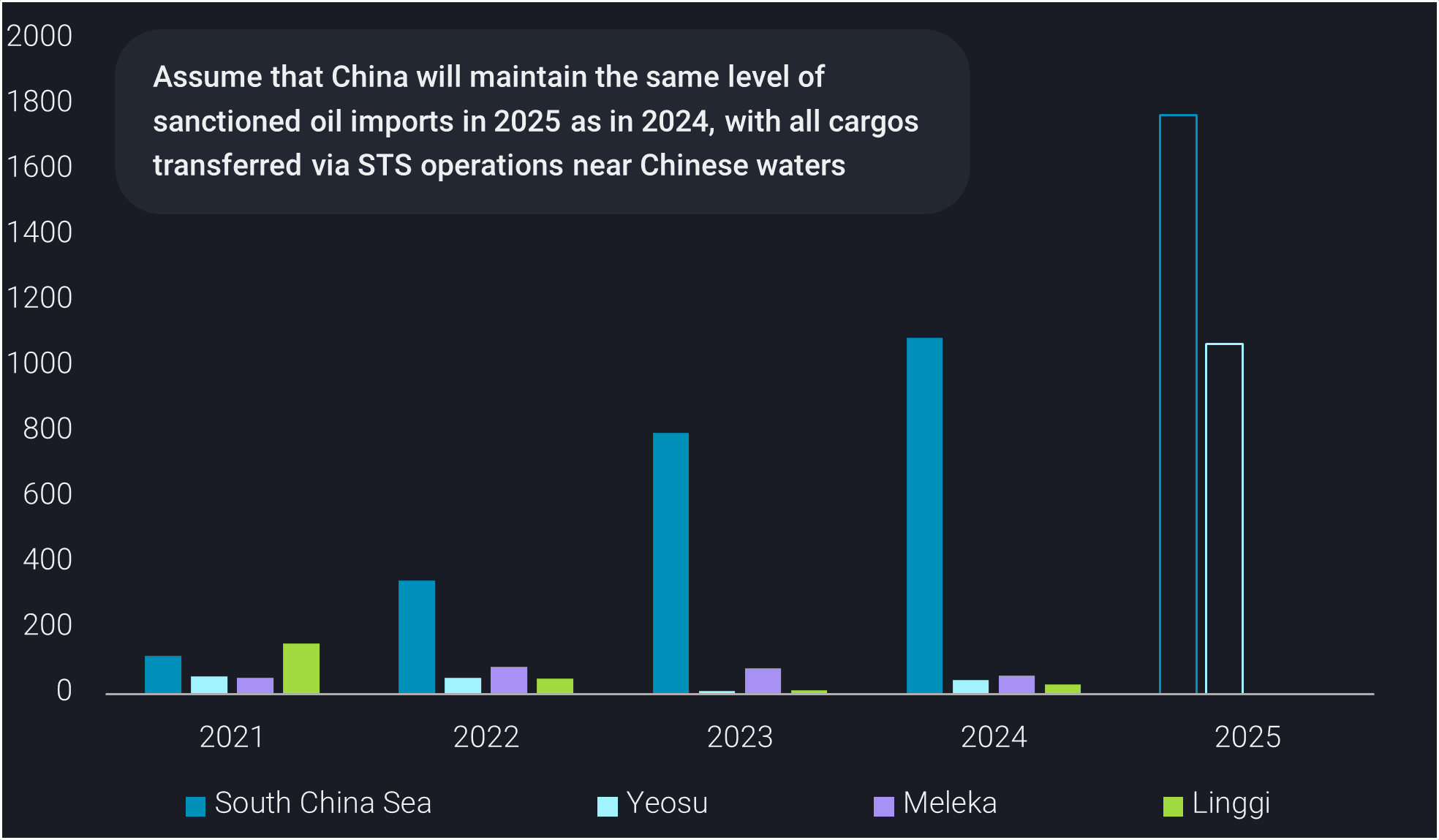

Shandong’s ban supports STS near Chinese waters

The recent Shandong ban, combined with U.S. sanctions on Russian tankers, has already slowed sanctioned oil tankers’ calls at Shandong ports.

The duration of this shipping disruption remains uncertain: on one hand, the implementation of Shandong’s ban is unclear, particularly after Beijing reiterated its strong opposition to U.S. sanctions following SPG’s notice. On the other hand, there is speculation that sanctions could be eased after Donald Trump’s return to power, or at least that the exemption period might be extended.

Meanwhile, some Shandong refiners have turned to non-sanctioned crude barrels, including pricier West African and UAE crude. However, the majority of Shandong teapots will likely continue to rely on more competitively priced sanctioned oil to protect already narrow margins due to weak domestic demand – hoping that imports can be maintained through ship-to-ship transfers near Chinese waters.

Potential interruptions to flows could lead to refinery run cuts, including an early initiation of spring maintenance schedules, rather than significantly boosting demand for non-sanctioned oil.

Nonetheless, the uncertainty in the market and the potential loss of supplies have boosted oil benchmark prices and mainstream tanker freight rates to multi-month highs in response to these recent announcements.