Europe’s flexible gas markets backfire in global energy crunch

Unprecedented gas price surge in recent months has tilted United Kingdom into crisis mode, but the problem is spreading across Europe and the rest of the world. This is launching the LNG industry into the middle of a colossal battle between European and Asian buyers for precious winter spot cargos.

Tightness in the global gas market has generated an unprecedented price surge in recent months of over 200%. Northeast Asian prices have gone beyond $30/mmbtu, or $162 on a barrel-of-oil-equivalent (boe). This has tilted various countries into crisis mode, including the United Kingdom, but the problem is spreading across Europe and the rest of the world.

As coal prices have kept pace with gas, and with a limited amount of idle oil fired power generation across impacted regions, major markets are now looking for alternate fuels but few options available. As a result, the LNG industry has found itself in the middle of a colossal battle between European and Asian demand for precious winter spot cargos.

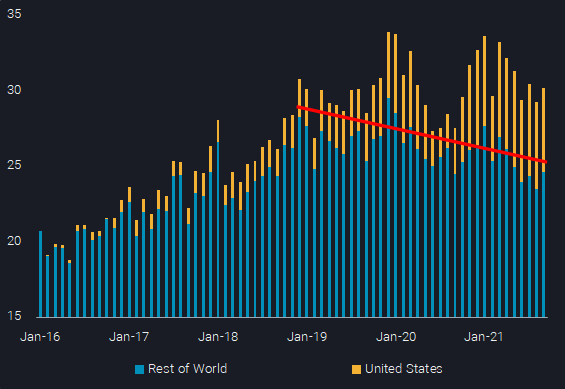

The oil and gas markets are currently suffering from the same fate, as a fundamental lack of supply has emerged and few producers are able to respond – the driving force behind the rising prices in both commodities. For LNG, the market recovered from the COVID-19 demand shock and late last year facilities reached full capacity again. The US has been the key contributor to growth in recent years, while in the decline in the rest of the world production has outrun new capacity investment since 2019. Whereas in the oil market, it is currently only Saudi Arabia and UAE that manage to raise production significantly.

Historically, Europe has maintained an advantage over Asian markets, with domestic production from the North Sea and Netherlands, plentiful pipeline gas from Russia, and benefitting from a highly integrated and flexible gas market. Notably, their large gas storage sites are capable of meeting peak winter demand with adequate injections throughout summer. These factors have frequently left Europe as a market of last resort for LNG flows, with few European utilities willing to pay a premium for LNG above Russian supplies.

Europe’s decision to liberalise its gas markets over two decades ago has provided huge benefits to gas users when supply was abundant, gas-on-gas competition fierce and gas hub prices were low. The largest suppliers, Norway’s Equinor and Russia’s Gazprom, were forced to transition away from long-term, oil-linked contracts – resulting in the vast majority of sales being priced on day-ahead and month-ahead gas hub prices. Currently less than 15% of Gazprom sales are linked to oil prices – leaving end users exposed to the record highs and extreme volatility in gas hub prices.

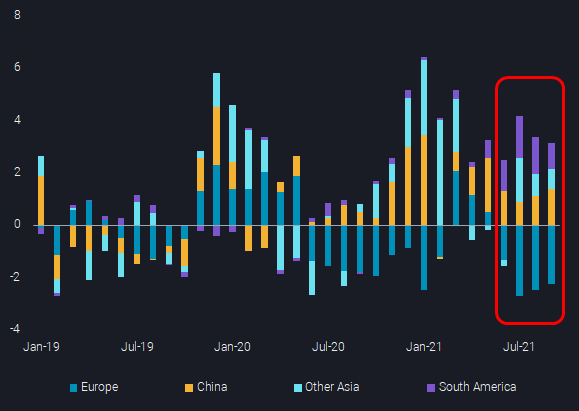

Since June, European LNG imports have been down by 20% based on pre-COVID levels, which is the most important period for underground gas storage injections. China’s increased LNG demand has been a considerable factor in the tightness of the global energy markets this year, being up 19% year to date. China is on track to add 14mn tonnes annually (mta) of demand versus 2020, this equates to 17% of Europe’s total LNG imports. But over the summer period it was actually South America that diverted at the margin cargos away from main buyers, including European storage sites.

LNG imports vs 2019 average for Europe, China, Other Asia, South America (mn tonnes)

As a consequence of market liberalisation and spot-linked pricing, European utilities have largely become price takers in global markets. Only 22mta of new long term supply contracts have been struck by European utilities over the last ten years – representing only 25% of total LNG imports. Half of these new contracts and the majority of legacy contracts are supplied with diversion rights or supplied into flexible portfolios with competing commitments across the globe. This leaves European imports highly exposed to tightness in the LNG spot market, which despite increased trading activity is still relatively illiquid and subject to large price volatility.

The geopolitical struggle over the Nord Stream 2 pipeline project has added more uncertainty to Europe’s gas supplies, as this project will provide a new independent route for 55bcm per annum (equivalent ~ 40mta of LNG) of Russian gas to Europe and reduce the need for existing Ukrainian gas transit capacity. The Biden administration removed the US sanctions on Nord Stream 2 project, allowing the pipeline to be connected into the German grid. But the wait continues, as the European Union’s lengthy regulatory approvals are expected to carry over into next year, particularly as Poland’s PGNiG opposes the application. Gazprom’s actions during 2021 have led to questions of their motivations, particularly as the lower Russian gas flows through Ukraine continue to add to market tightness, and Russia is the largest beneficiary of high natural gas prices in Europe.

Russia’s influence over European energy security has been long debated. Over recent years, eastern Europe has taken action to diversify energy imports, with LNG terminals constructed and long term agreements secured by Poland, Lithuania and Croatia to reduce the risk of dealing with a single supplier. Imports into these nations have increased to 4.4mta in 2020 and have been sustained during 2021, despite the record spot prices. The majority of LNG imports into the rest of Europe are flexible supply contracts, where cargos are diverted to the highest priced markets – adding little to security of supply for Europe.

Regardless of the winner of the struggle for winter LNG supplies or the extent of the damage from this looming global energy crisis, energy security will become an even more pressing issue for Europe. A review of the vulnerability of its gas markets is likely to follow, with a particular focus on the strategic nature of gas inventories and the market’s evolution towards flexible short-term trading as a determinant of energy security.

At a time when energy transition is driving large investments into renewable energy, this crisis is emphasising the importance of maintaining resilient natural gas supply chains to support decarbonisation targets and provide a backup for the intermittency of new energy sources. The looming question is who will continue to commit to natural gas and LNG investments with relatively low returns, long paybacks and an uncertain place in the future energy solution.