Should the US Colonial Pipeline network remain down for more than a few days, the nation’s East Coast and Southeastern markets will start to see supply hiccups and related price spikes, while Gulf Coast refining centers will scramble to place cargoes alternatively.

-

Traders may find opportunities to divert seaborne clean product cargoes from other destinations toward US Atlantic Coast (PADD 1) ports, and to sell cargoes from Caribbean storage into the region.

-

South American importers of US Gulf Coast (PADD 3) products (primarily diesel) could purchase cargoes at lower-than-normal prices if sellers are incentivised to clear accumulating supply.

-

Niche trades moving oil products by truck to landlocked Appalachian markets may also become profitable.

The biggest x-factor in these “disruption dynamics” is the potential for a waiver of Jones Act rules, which would open the arbitrage between the Gulf Coast and the East Coast and undermine the economics of the aforementioned trading opportunities.

-

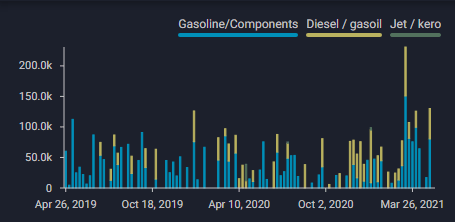

The US East Coast region has about 65mn bbl of gasoline on hand, equivalent to about 20-25 days of forward demand cover, while figures for diesel and jet fuel shoud be higher according to EIA data. But inventories will draw down fast if pipeline supplies stay offline for long, and for some local markets forward cover will be significantly lower.

-

The main offset for disrupted gasoline flows via pipeline is imports primarily from Europe, but also ports at eastern shores of the Americas, such as Brazil, the Caribbean or Canada. The voyage time from Europe is about 14 days, with potential supplies from East of Suez taking much longer. The longer the Colonial outage goes on, the more likely new cargoes are booked to supply the US East Coast, to refill storage.

-

There is also the option to divert vessels that are already in transit. For that purpose we looked at all gasoline, diesel and jet fuel cargoes in transit to eastern shores of the Americas (excluding the US). Out of those we identified about 20 cargoes that could realistically be rerouted, carrying about 6 million barrels of fuels (primarily gasoline). Further alternative supply options include Caribbean storage hubs that have taken a number of deliveries recently and are only 2-6 days of voyage time away from relevant PADD1 ports.

-

Furthermore, we are currently tracking 36 tankers carrying gasoline and blending components toward PADD 1, two thirds of which are heading for New York Harbor. With the southeastern parts of PADD 1 particularly reliant on Colonial supplies, we think five ports between New York and Jacksonville are likely to play an important role in supplying local markets: Philadelphia, Charleston, Savannah, Baltimore and Yorktown.

-

On Sunday night, our algorithms detected a first gasoline diversion toward mid-Atlantic markets at greater risk of developing shortage. Litasco-chartered Tavrichesky Bridge, carrying 370,000 barrels of gasoline, diverted away from New York toward a new destination of Yorktown, Virgina, Close to the Colonial-supplied cities of Richmond and Norfolk, Yorktown has received few clean product cargoes before now.

CPP Imports of five ports between New York and Jacksonville that recieve MR2 tankers (b/d)

-

Why can’t PADD 3 refineries just supply more to the markets in shortage? The big stumbling block is regulatory in nature: The 1920 Jones Act is a federal law that says only ships that are US built, flagged and majority owned can transport goods between US ports. There are only about 57 oil tankers that meet this standard, called “coastwise-qualified,” and many of them are off the market, leased on long-term time charter. So the supply of tankers that can transport oil between US ports is very limited.

-

While the pipeline outage persists, the prospect of Jones Act rules being waived is a huge x-factor for the oil market. A waiver would enable foreign flagged ships to move fuel cargoes between US ports – not only newly scheduled loadings, but also foreign tankers originally destined for international destinations that could then be re-routed to US ports. We count about ten tankers that have recently left the US Gulf Coast for southern destinations, that could in theory be rerouted. In general, the US oil industry tends to support these waiver requests during oil market disruptions, while the US shipping industry has usually opposed them.

-

The most recent oil-related Jones Act waiver was in September 2017 following disruptions to Gulf Coast refineries caused by Hurricane Harvey and in anticipation of Hurricane Irma in the Caribbean. A seven-day waiver was granted to move refined products shipped from New York, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Louisiana to South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, and Puerto Rico.

-

Two federal agencies can initiate Jones Act waivers: Department of Defense (DoD) and Department of Homeland Security (DHS). In the first case, a waiver requested by the DoD is automatically approved. Requests made through DHS are more discretionary – while still assessed as whether necessary for the national defense, the litmus test has been to determine whether the supply of coastwise-qualified vessels is sufficient to meet the challenge.

-

Back-to-back Gulf Coast hurricanes in 2005 illustrate the importance of consensus in Washington for waivers to succeed. After Hurricane Katrina, both the oil and shipping lobbies supported a waiver with the understanding that coastwise-qualified tanker supply was not enough, and the waiver was granted. But after Hurricane Rita struck a few weeks later, the maritime industry protested, claiming US vessels could handle the job of oil transportation. The waiver request was denied.

-

Another important nuance for oil traders is whether gasoline blending components are explicitly included in any waiver. Following 2012’s Superstorm Sandy that disrupted East Coast markets, a three-week Jones Act waiver was granted on finished gasoline only, not on blending components. The 2017 waiver following Hurricane Harvey stayed silent on the matter of blending components.

-

The longer the situation continues, we doubt it will be more than a few days, the bigger will be the negative impact on US Gulf Coast refining if the Jones Act is not waived. In turn, European refineries would be the main beneficiaries in this scenario. If the situation is resolved within 1-3 days, the repercussions will ultimately be limited with the reallocation of held-up barrels likely to pass smoothly within a few weeks.

Want to get the latest updates from Vortexa’s analysts and industry experts directly to your inbox?

{{cta(‘cf096ab3-557b-4d5a-b898-d5fc843fd89b’,’justifycenter’)}}

More from Vortexa Analysis

- May 6 2021, China’s crude imports slow. Due for an imminent rebound?

- May 5, 2021 Saudi Arabia ramps up DPP imports in April

- Apr 29, 2021 Oil markets on track to recovery? Only time (and freight) will tell

- Apr 22, 2021, Global gasoline outlook 2021

- Apr 21, 2021 Latin America road fuel oversupply growing in April