European oil resupply is clearly underway but biggest steps yet to be taken

Europe has sucessfully made first steps in scaling back Russian oil imports and resupplying from other sources. But only about one third of the diesel challenge has been managed so far, already leading to record pricing. Global refining is severely constrained.

About 70 days after the invasion of Ukraine by the Russian military, Europe (excluding Turkey) has cut Russian crude and product imports by a bit more than 20% or 1mbd, and managed to replace these volumes with non-Russian barrels. Pricing patterns suggest that it is relatively easy for most European players to source alternative crude oil, while record diesel cracks pretty consistently above $50/b are testimony to the much bigger challenge a potential loss of the Russian motor fuel poses for the world economy. With most refiners already maxing out diesel yields and overall refining runs, the global oil supply/demand picture will have to be solved in diesel and other clean products rather than crude, changing the players to look at for help.

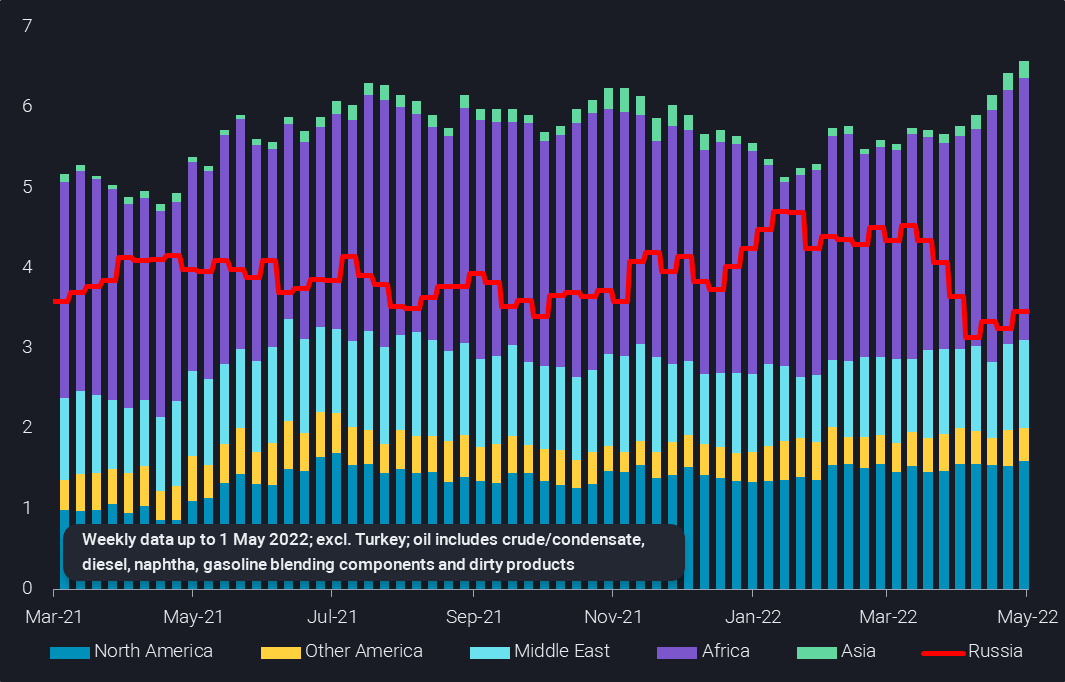

In the four weeks to 1 May, Europe (excluding Turkey) imported 3.5mbd of Russian crude oil and products. While the trend has been slightly increasing over April, this figure is still 1.25mbd or 28% lower than the inflection point in the four weeks to 16 January. Since then oil imports from all alternative sources have increased by 1.45mbd or 26%, leaving the continent actually slightly better supplied. Most of these changes took place since mid March (see chart).

Crude oil accounted for most of the changes, which in turn were driven by additional supply from Africa, to the tune of 850kbd from a low point in the four weeks to 16 January. Relative to that time stamp, supplies from the Middle East and North America are up by about 100kbd, with more oil on the water for delivery in the near future.

If Europe were to replace all seaborne Russian crude imports, at 2.2mbd in the four weeks to 1 May, it would have to boost imports from non-Russian sources by about 40%. This looks possible, especially if Russian crude were to continue to make inroads in the Asian market. Seaborne exports from the European side (Arctic, Baltic, Black Sea) to Asia hit 1mbd in April, up eightfold from less than 130kbd in February.

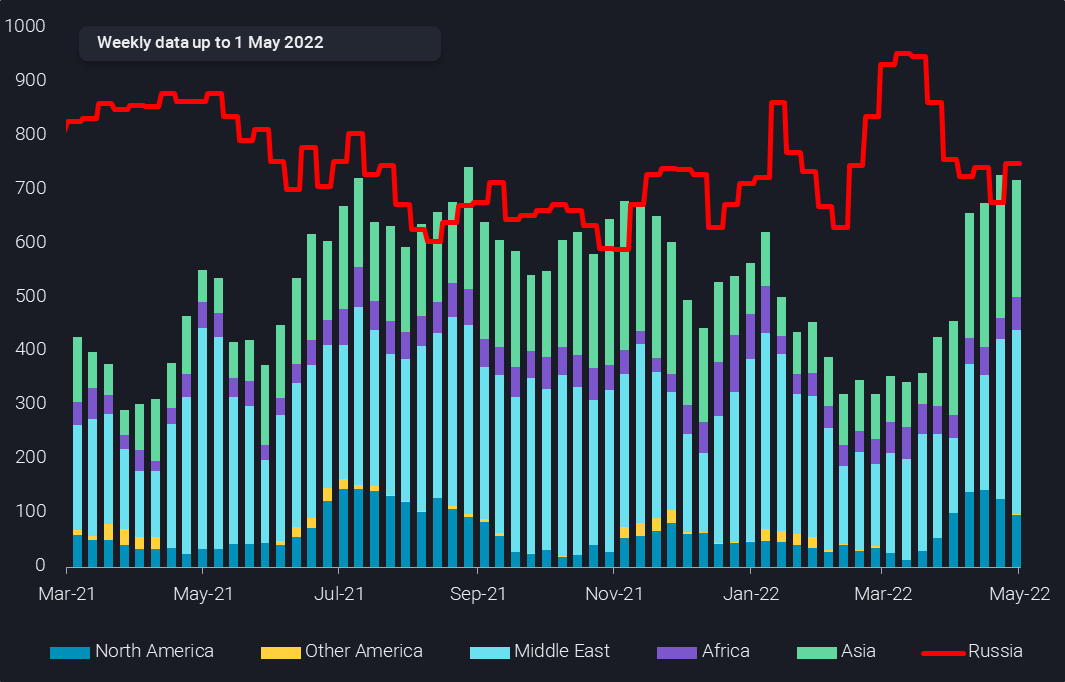

The story is very different for diesel. To start with, European imports of Russian diesel still stand at 740kbd, equal to the average observed from Jan 2021 to Feb 2022. Only when compared to extraordinarily high levels seen oveImage r late Febuary/early March, European imports of Russian diesel are down by 200kbd or 20% recently. Nevertheless, Europe has attracted an additional 350kbd of non-Russian diesel since mid March, coming from Asia (160kbd), the Middle East (120kbd) and North America (70kbd).

This effort has raised the share of non-Russian diesel in European imports to close to 50% from slightly above 25% in mid- March (all on a 4-week average basis). That is some achievement, but it pushed diesel cracks regularly above $50/b along the way, leaving also the regional Asian and American markets very tight in products.

To get rid of Russian diesel altogether, the effort would have to be doubled in terms of boosting alternative supplies, and a further sharp appreciation of diesel and other clean product cracks is very likely to come along with it, especially if Russia is forced to curtail product exports further.

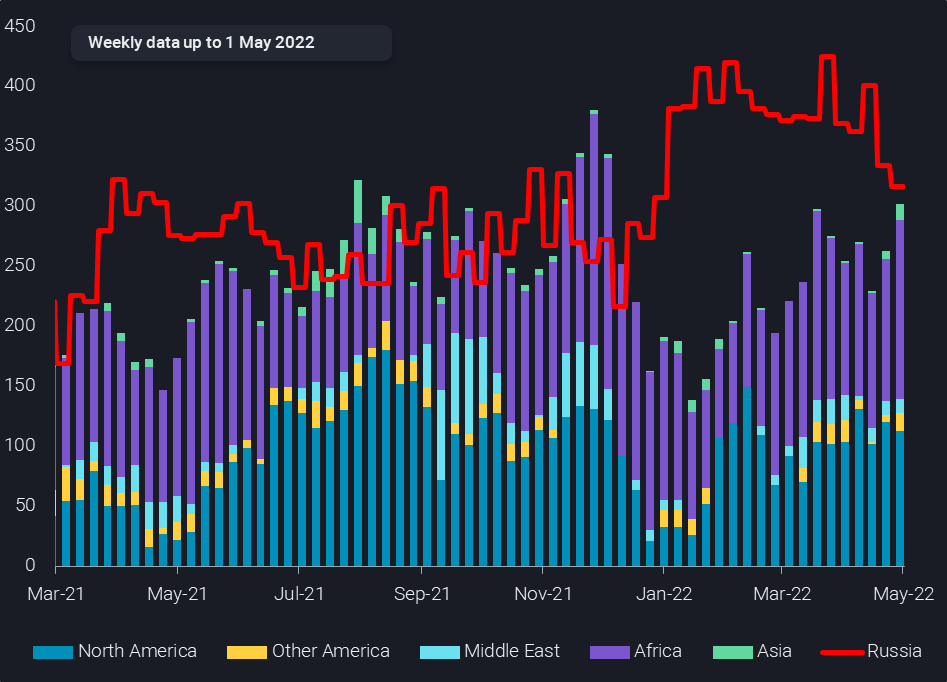

In the light of global product tightness, it is interesting to see that Europe is currently accumulating light-end imports (mostly naphtha). Firstly, Europe has only scaled back imports of naphtha and gasoline blending components from Russia by 20% or less than 100kbd. Buyers in Asia and Americas have scaled back loadings from Russia for these products by 80%, driven also by poor petchem demand in Asia. But Europe has also increased imports of light ends from alternative suppliers, especially of US-stemming naphtha. Two thirds of all these supplies, including the Russian ones, are going to the ARA hub, surely in many cases for blending finished gasoline. This raises interesting questions in the light of recent announcements from BP and Shell, asking for products not containing any Russian components from here on.

Very bullish outlook for motor fuels

In conclusion, the key challenge for the European market remains to substitute Russian diesel supplies, which is illustrated by the fact that only one third of that path is gone so far, pushing diesel cracks to $50/b.

Global refining capacity has already been tight in 2019. More than two years later, we have seen a number of refinery shutdowns during the Covid era, while demand is now slowly zooming in on pre-Covid levels. But we are in the process of scaling down supplies from Russia’s big refining industry, while China is politically curtailing product exports and therefore the use of spare refining capacity from a global perspective. China and Russia account for 20% of global refining capacity, and likely a solid majority of realistically operable spare refining capacity.

Compared to crude oil, the mechanisms to balance tight refined product markets are much more limited, especially with respect to the lack of surplus inventory (SPRs), (OPEC+) spare capacity, and the relatively responsiveness of the US shale industry. With not much room for increases in refinery throughput levels, yield shifts are usually a tool for rebalancing, but with the US/western driving season coming up and air travel picking up as well, gasoline and jet fuel have to compete with diesel for marginal molecules. Residues are also pricing at record levels, given lost Russian supplies and power generation demand. That leaves currently only naphtha with less bullish fundamentals, but that will fail to ease the heat on other products in a meaningful way.

While the upside for crude prices is challenged from various perspectives, it is much less clear what will keep fuel prices/product cracks from rising much more in the coming months. A drastic policy shift in China, allowing to boost domestic refinery runs and product exports, could make a meaningful difference, but the country has evidently different problems right now. Otherwise, it can only be hoped that some of the outdated simple capacity, such as in Mexico can be dragged back into the market. Such plants would however produce a big share of feedstocks and intermediate products, rather than finished fuels, requiring respective financial incentives.