The Biden administration announced today a historical Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) release, but rather than cooling oil prices it led to a spike, at least in the short term. Let’s investigate why there may be some reason for this reaction, other than the usual “buy the rumour, sell the fact” rationale.

The SPR release announced today consists of 50mb from the US SPR, accompanied by SPR draws in China, Japan, India, South Korea and the UK that may add another 20-30mb to the release program (Bloomberg). It is unusual from at least three perspectives:

- The focus to lower (manipulate) prices, rather than to cope with a concrete supply outage

- The size of the program

- The fact that it is coordinated outside the usual IEA framework between six consumer countries

Geopolitical repercussions

The coordinated SPR release among consumer countries is the culmination of widespread complaints over recent months that OPEC+ was too hesitant and slow in adding barrels to the market, allowing prices to surpass $80 per barrel. We explored last week that these complaints are understandable when looking at overall OPEC+ exports, which only picked up as recently as last month.

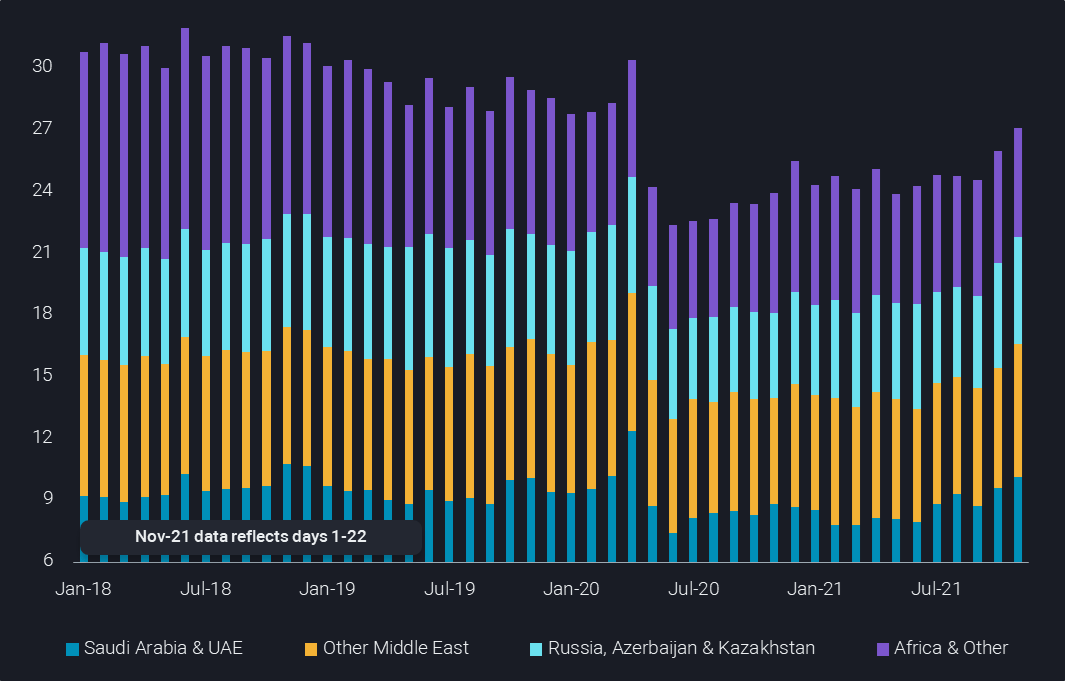

But this view at the entire group hides a sharp divergence between different members. Rather than being unwilling to produce more oil, many member countries were evidently unable to hike production. On the other hand, Saudi Arabia and the UAE clearly upped their supplies, even beyond the agreed path, from July onwards. Russia followed a couple of months later.

OPEC+ crude oil exports by country group (mbd)

The question is now how OPEC+ will react to the US-led action, which clearly risks souring US-Saudi relations, but also US-Russian relations further. The OPEC+ view on the situation is surely different, given that even stronger inflationary pressures come from the natural gas market, while supply chain issues are also to blame. The group may well see a lack of appreciation of its market stabilisation activities over recent decades and last year in particular, involving the costly holding of spare capacity. It will also point at the uncertain demand outlook and widely expected long crude balances in 2022, including those from the IEA, a consumer-focussed agency.

The net-effect of the SPR releases

While at first glance, the SPR release appears massive, it shrinks rapidly when widening the perception over a longer time horizon. SPR releases may only start in earnest in 2022, and could easily be dragged out over six months. If we assume a 75mb draw over 6 months, equivalent to about 400kbd, this can be negated by OPEC+ by merely pausing their target output increase program for just one month.

OPEC+ has a mechanism already agreed to allow for a pause in the production increase for up to 3 months, and this could be easily triggered at the next meeting – making a case for this by reference to the latest Covid-19 wave in large parts of Europe.

Secondly, the US-part of the SPR release is actually a net-zero-sum gamble. It involves 18mb of already agreed draws, just being brought forward, and a 32mb exchange program, meaning that the drawn barrels have to be replaced with fresh ones in the not too distant future. Other participating countries will also have to refill their SPRs later on, as otherwise they risk being less well positioned against any outages going forward.

The wrong signal for upstream investments

What can also be questioned, is whether the SPR release gives a welcome signal to US shale producers and anybody else who is considering investing in upstream capacity. The latest policy move may be misguided by the perception that the problem is producers’ unwillingness to produce more oil, as opposed to the inability amid growing decline rates and unattractive investment conditions.

The current episode may serve as a reminder of how dependent the world economy is on traditional energy sources. But if we realise how much we need oil, gas and coal over the coming years (and decades), we should also make sure there is sufficient investment, rather than cornering more or less reliable producer countries with SPR releases. It is good tradition that SPRs are used to cope with short-term supply outages, rather than longer-term market management. Anyway, SPRs become quickly pretty tiny when compared to long-term supply needs.

Takeaway

Overall, the SPR release is unlikely to materially change the S/D balance over the coming months and 2022 as a whole. The initial price reaction may be a reflection of this, as well as a failure to cope with the true oil market issue – ensuring sufficient investment in maintaining existing and adding new production capacity.

What could ultimately turn the story bearish is the implicit message how vulnerable the world economy is to high energy prices. The current action by six major countries may tell more about the state of their economies than approaches to oil market management. And poor economic development neither serves the interests of consuming markets nor producer countries.

Each week, Vortexa Market Analysts produce exclusive reports highlighting product flows in Asia, Europe, and Americas. Receive these directly to your inbox, and see how effective data using Vortexa Analytics can be. Sign up here!

More from Vortexa Analysis

- Nov 23, 2021 Asia’s gasoline cracks make an unexpected U-turn

- Nov 18, 2021 Asia’s crude appetite sweetens in November

- Nov 16, 2021 Musings on OPEC+ spare capacity

- Nov 11, 2021 Tonne-miles need to pick up to sustain rally in dirty freight rates

- Nov 10, 2021 Does supply provide a cure for record LPG prices?

- Nov 10, 2021 Global diesel market braces for tight winter as inventories draw

- Nov 4, 2021 What’s behind Asia’s gasoline crack surge?

- Nov 3, 2021 A sweet-sour situation for OPEC+

- Nov 2, 2021 China scrambles for diesel to avert another power crunch

- Oct 28, 2021 FSU fuel oil exports decline in October

- Oct 26, 2021 Crude floating storage shows diverging trends